I'm very glad I chose to work with In the Skin of a Lion as it had been a pleasure reading, discussing and analyzing it with two amazing group members. Thanks Jade and Paul!

This class overall has been an adventure: thank you Erika, for letting us know through your incredibly creative ways of teaching what it means to learn while thoroughly enjoying the process. This course opened my eyes in many respects. I've mentioned before that I've never found First Nations culture and history to be interesting; however, I do not exaggerate to say that I now find it fascinating, and I have to thank Green Grass Running Water for this. Like Michael Ondaatje who presents the immigrant's side to Canadian history, King reminds us how critical it is to allow our eyes to see. This course brought into light everything I was questioning already about Canada's identity as well as my own, and I realize now that I am part of an enormous population of Canadians who struggled and are still struggling to find footing in the dynamic of our great country. I'm looking forward to extending what I've learned beyond the scope this of classroom, to open other people's eyes in front of something conventionally unseen, and to ultimately add voices to the strict repertoire of stories we collect closely around us for safety. Maybe it's time to see the truth as a lie, and the lie as a truth. If we never venture into these dangerous waters, we may never be safe.

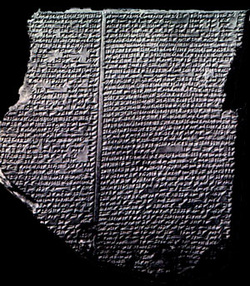

in the skin of a lion. [ The Epic of Gilgamesh] Gilgamesh is described as a wise and accomplished king who is determined to conquer mortality upon witnessing the death of his beloved friend and companion. He ultimately fails, realizing that the only way mortals can achieve immortality is through the establishment of civilization and culture. Ondaatje uses a quotation from this epic as the title of his novel to draw our attention to the similarities between this ancient hero and the one he presents: Patrick Lewis. As Ondaatje becomes each of his characters and each of his characters becomes an alter ego for Ondaatje, as "each person had their moment when they assumed the skins of wild animals, when they took responsibility for the story" (157), the writer participates with the workers in building the viaduct and the water filtration plants. An historical figure, Commissioner of Public Works Rowland Harris, the powerful master builder, is one of the most surprising alter egos for the writer in this novel; like Harris, Ondaatje dreams of wonderful structures and then brings them into being; like Harris, he looks at Patrick and identifies him as the ancient hero Gilgamesh.It's interesting to note that Patrick rarely sees himself as a hero, but instead as a "watcher, a corrector...He had lived in this country all of his life. But it was only now that he learned of the union battles up north...And all of his life Patrick had been oblivious to it, a searcher gazing into the darkness of his own country, a blind man dressing the heroine." [In the Skin of a Lion p.157] Gilgamesh's fight with the lions in the night is both an act of self-preservation and an act of anger that the beasts still enjoy life while Enkidu is dead. Similarly, Patrick Lewis's attempt on Commissioner Harris's life and the Waterworks grows out of his anger at Harris's continued success and power while Patrick's love, Alice Gull, is dead. Harris retains his power as he orders the explosives removed, but, in recognizing Patrick as Gilgamesh, he recognizes the power and importance of the workers, the underlings; the unknown man who fails in his subversive mission, whom Harris previously designated as "among the dwarfs of enterprise who never get accepted or acknowledged" (238), is now identified as a hero.

Can Commissioner Harris be seen as a type of hero as well? It's true he neglects the workers and does not acknowledge their contribution until the end of the novel but, as no story should "be told as though it were the only one", perhaps we should see it from his point of view. He dreams of bringing the viaduct into life, infrastructures crucial to the growing city of Toronto. Maybe he chose not to see the workers, because he knew there was no other way. Because for every triumph there exists defeat. Perhaps later on in the book Harris finally realizes that his ignorance of the workers, be it deliberate or involuntary, will not go unnoticed without consequences. One of the themes of The Gilgamesh Epic concerns harnessing the power of the strong so that, instead of harming society, it benefits it. For Gilgamesh, the loss of his comrade, his period of mourning, and his learning the secrets of the great Flood turn him from a wild, strong youth into a responsible ruler. The definition of the hero changes from the man of sheer physical strength to the man with special knowledge of the human condition, of death and survival, as expressed in Enkidu's death and the story of the Flood. In the scene at the puppet theatre, Patrick sees himself as the hero, the rescuer, as he rushes on to the stage to save the exhausted Alice. As he joins with the workers, his power resides in his knowledge of explosives. At the end of the book, he has acknowledged that he is not the hero/rescuer. He has perhaps learned what Van Nortwick sees as the main lesson of The Gilgamesh Epic:“... the poem suggests that Gilgamesh must learn to see himself not as preeminent among men, but as part of a larger whole, ruled by forces often beyond his ability to control. Rather than challenge his limitations, he must learn to accept them and live within them: maturity requires humility which requires acceptance, not defiance, not denial.” (37)Here it is suggested that given Patrick's circumstances, it is not possible for him to be a hero in the sense of Commissioner Harris because various societal structures do not allow him to. This does not mean, however, that he is not a hero. "Alice had one described a play to him in which several actresses shared the role of the heroine. After half an hour the powerful matriarch removed her large coat from which animal pelts dangled and she passed it, along with her strength, to one of the minor characters. In this way even a silent daughter could put on the cloak and be able to break through her chrysalis into language. Each person had their moment when they assumed the skins of wild animals, when they took responsibility for the story." [In the Skin of the Lion p.157] The silent Patrick is just as heroic as the man who brought the viaduct from his imagination to reality. We need to recognize that there is no absolute heroism, because it all depends on who tells the story and how it is told. In acknowledging Patrick Lewis as hero, as Gilgamesh, Commissioner Harris cedes power to those less politically powerful than himself. By calling for a nurse with medical supplies rather than the police, Harris accepts his role in the death of Alice Gull and accepts his "amateur" status (242) in the midst of the truly powerful. In acknowledging his own role in the accident that killed Alice Gull, Patrick ends his defiance and denial, freeing himself to journey toward Clara in the final chapter of the novel.

[source: link to similarities]

All of the puppets looked stunned. Feet tested air before each exaggerated step was taken on this dangerous new country of the stage. Their costumes were a blend of several nations. It was five minutes into the dance before Patrick realized that the large puppet was human. And this was only because the dancer moved out of his puppet movements and began to twirl in gestures impossible for wood. [In the Skin of a Lion p.116] Immigrants were recruited, used, then flung carelessly to the backs of powerful minds. You forgot us....I fought tooth and nail for that herringbone.You fought. You fought. Think about those who built the intake tunnels. Do you know how many of us died in there? [In the Skin of a Lion p.236] The articles and illustrations he found in the Riverdale Library depicted every detail about the soil, the wood, the weight of concrete, everything but the information on those who actually built the bridge...Official histories and news storied were always soft as rhetoric, like that of a politician making a speech after a bridge is built, a man who does not even cut the grass on his own lawn. [In the Skin of a Lion p.145] The large figure began to distinguish itself from the others. It became a hero not by size but by gesture and the detail of character. [In the Skin of a Lion p.116] Really. Are they everybody's heroes? Are they "Canadian" heroes? Where are they, in history books? In news articles? They're barely visible. Funny, to call them visible minority.

I gather on the bus during the early hours of the morning. I stay awake to keep the words company. Michael Ondaatje`s effortless transformation of language into imagery is exquisite; I find his writing to be stunningly poetic, like listening to a score of music with the harmony perfectly entwined within its melody. I find the plot of this novel to be vague and unfocused, in stark contrast with the sharp crispness of the arrangement of his words. I do enjoy this level of uncertainty and freedom his story presents for his readers, permitting us to go along our own tangents of thought, mental paths given rise by our own unique collection of stories we have gathered since birth. Stories are told through language. No language has the capacity to be translated completely into another one, however similar the two are due to geography and culture. Stories are hence only pure and "right" when they are told in the language it was born within. Canada is home to more languages than I can count, and in turn to more stories than one person can tell. ...he walked everywhere not hearing any language he knew, deliriously anonymous. [In the Skin of a Lion p.112] Language, to an extent, is the culture that gave rise to it. Four women and a couple of men then circled him trying desperately to leap over the code of languages between them. [In the Skin of a Lion p.113] Immigrants arrive in waves to Canada in the 1930s, foreigners willing to call this land home, willing to learn its language so they can listen its story.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed